22nd August 2025

Traditional fingerprint analysis can help police forces match a mark left at a crime scene with a suspect’s print. But a pioneering new molecular fingerprinting technique can tell investigators this and much more – from identifying if the person has come into contact with blood, drugs, cleaning products or other materials, to associating a suspect’s fingermark with a victim’s blood.

We caught up with Sheffield Hallam University’s Professor Simona Francese, an internationally renowned researcher in forensic and bioanalytical mass spectrometry, on how her research can be implemented by forces.

Pioneering research

Until Professor Francese’s research began in 2008, fingermarks left at a crime scene were only analysed as a means for biometric identification. Investigators take an image of the marks to visually compare against suspects in the case or wider fingerprint databases. But fingermarks themselves are comprised of molecules – a fact that’s exploited by the pioneering technique.

But visual comparisons provide investigators with a good success rate, so why is a molecular approach needed? The answer according to Prof Francese lies in its flexibility and detail:

“CSIs generally use one image of a print, or if they use sequential processing, a handful, but if those techniques don't work or only give a partial unidentifiable print, then they are stuck. Instead of optical, photographic images we take molecular images to visualise where certain molecules are distributed,” she says.

“The molecular technique can visualise hundreds of molecules in one analysis, so theoretically we can provide hundreds of images of the same print or increase the ridge pattern coverage by stitching together different patterns from different images.

“Furthermore the recovery of storytelling molecules in their fingermarks may provide intelligence on the suspect themselves and their actions prior to or during the perpetration.”

As Prof Francese says, the molecular analysis doesn’t prevent traditional fingerprint analysis taking place:

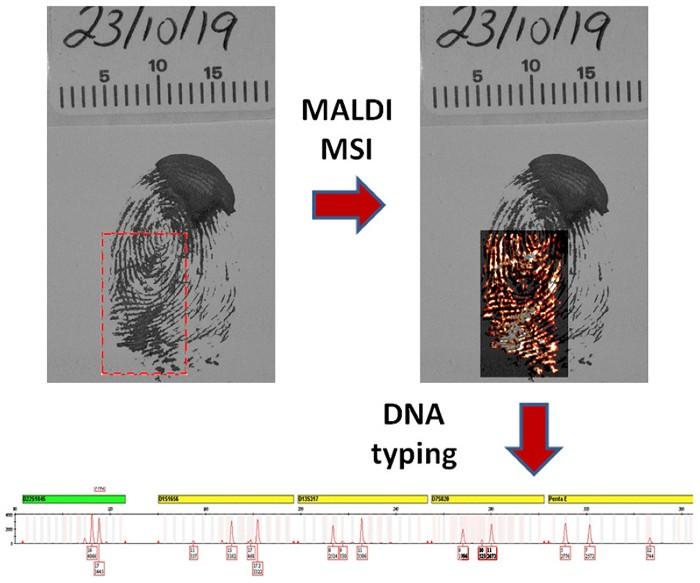

“The bulk of our research since beginning has been on producing a technology that is compatible with existing fingerprint visualisation techniques. It’s not one or the other. Whilst it is important to gain more information on the person, the crime, the circumstances, it is paramount that the technology is compatible with current visualisation methods used at the scene and labs. We have demonstrated several times that the technology can be used in operational workflow, both in pseudo-operational trials and within live casework. Recently, we have also observed that its application does not prevent DNA testing from blood marks previously visualised with a routine blood enhancement technique.”

Technology in practice

So, the technique can help forces see more detailed information from fingermarks left at a crime scene, but how does it actually work?

The technology is known as Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Mass Spectrometry and it can work in either Profiling (MALDI MSP) or Imaging modes (MALDI MSI). It is normally used to map pharmaceuticals and biological molecules within tissue sections. Applying MALDI MSI to fingerprints, though, can give investigators a rich picture of a suspect’s activities at the crime scene and their broader lifestyle in association with their biometrics.

For example, a fingerprint left at a crime scene may contain traces of blood which aren’t visible to the human eye and may only be presumptively tested with the current techniques; it will also contain DNA which can be typed against a suspect. Applying the MALDI MSI technique at the crime scenes means investigators can: confirm the presence of blood, tell whether it is human or not, provide extra information for example on haemoglobin variants (they have low incidence so can help narrowing down the pool of suspects) as well as enabling further DNA testing.

As the technology can definitely identify semen (and is being optimised for the reliable detection of other biofluids too), the police can also identify which biofluid the DNA originated from thus helping with determining the nature of the crime.

Prof Francese says: “Blood is a vital form of evidence. But the presumptive nature of the test cannot conclusively determine its presence, and confirmatory tests are destructive of fingermark evidence. For example, depending on the test used, protein-containing biofluids such as semen as well as unrelated matrices like bleach will test positive for blood. Making the wrong biofluid attribution changes the nature of crime changes.”

In relation to the importance of confirming the presence of blood and determining its origin, she points to the infamous case in which Susan May was convicted of murdering her aunt in 1993 in Greater Manchester, and spent 12 years in prison until her own death. The case rested on “bloody handprints” left on a wall, which were said to link Ms May to the crime.

However, a 2013 report published by fingerprint expert Arie Zeelenberg found the “bloody handprints” were not in fact blood, and stated instead “there is overwhelming evidence that they were not comprised of blood but instead of sweat and a minor residue of another unknown substance.” As Prof Francese says, the nature of crime changes entirely. If that was blood, it would have been crucial to verify Ms May’s statement that she had handled raw meat in the morning to prepare lunch for her aunt.” Prof Francese adds that her method for confirming the presence of blood and determining its origin has undergone pre-validation in a blind study.

Wide-ranging potential

The rich information available from molecular analysis means that forces can not only be supported in the reconstruction of the fingerprint ridge pattern for identification purposes but also facilitated in building a picture of a suspect’s lifestyle and activities.

“We asked ourselves, what could these molecules tell us about the person who left the print? Recently we have been able to show that the technology can determine the sex of an individual from their fingerprint with 86% predictive power. This capability could be exploited in triaging crime scene marks as part of the forensic strategy.

“This technology could indicate if the person was a drug dealer or drug user. If we find traces of the drug intact in their fingerprint but don't find its metabolites in the body, then it's more likely the person has dealt drugs than taken them.

“And again, this applies not only to drugs but medications, hair and cleaning products, condom lubricants, etc. We can provide molecular images of a fingerprint which show the presence of any of these substances – and any of these could be important in a case.”

Case study: West Yorkshire Police

Prof Francese also stresses that the MALDI MSI technique is already being used in operational policing, not just in the UK but internationally. “It’s not an academic exercise,” she says, “it works in the real world too.” We have been able to tell the police from a 26-day old mark that the suspect had most definitely consumed cocaine contextually with alcohol, with the latter information not being recovered from standard investigations.

One early adopter to trial the technology was West Yorkshire Police, via the four-force Yorkshire and the Humber Regional Scientific Support Service. Neil Denison, Regional Director Of Scientific Support, says:

“Simona has done a lot of work that has opened up opportunities we never thought existed in fingerprints. We’ve worked very closely with her, showing her how the technology could be applied in real-world cases, and helping us see the opportunities around intelligence. From visiting our labs and crime scenes, she’s been able to prove the technique does work alongside other recovery processes.

“The science is really interesting, and all of the intelligence it offers about an offender from their fingerprint at a crime scene may be useful in some circumstances. In future, the golden nugget would be to actually age a fingerprint. Once we can say how long a mark has been there, that would be very useful when a case goes to court. In any case, all our Area Forensic Managers are aware of the capability and it’s great to know the door is open and we can access it when a case requires.”

The Last Word

By all accounts, the technique spearheaded by Prof Francese and the Sheffield Hallam University team is pioneering.

“One group in the US had published in 2008 on a different technology showing the potential to use molecular information contained in fingerprints but this was poorly followed up. Our first paper using MALDI was published shortly after. Now the volume of knowledge is growing every year. Often you publish a paper then move on, but we’re taking different approach by expanding capabilities, the operational implementation and versatility of the application of MALDI to fingerprints rather than diversifying the applications of MALDI in areas different than forensics. It has really been a massive 13-year journey.”

But for all the opportunities the technique promises, more work needs to be done to raise awareness and scale-up the volume of cases where it’s deployed. Prof Francese’s last word is a plea to forces:

“We’ve been discussing this technology for years, but a lot of policing doesn't know about it, so we need to spread awareness and at the same time, we need answers to the questions of what do police need to become more confident in exploiting this opportunity? What do forces need to try-out and embed this?

“The more engagement we get, the better the technology will be. For example, how many times is it successful in police casework? We can’t say yet as we haven't analysed high volumes, and fingerprints are compositionally very variable due to a combination of intrinsic characteristics of the donor (variable as well), time since deposition, environment, surface of deposition and visualisation technique applied. Hopefully we can all work towards that together.”

Meet Simona at FCN’s Research Festival

To hear more from Simona about her research and ask your own questions, why not register for the inaugural virtual FCN Research Festival. Taking place w/c 6th September, the event brings together the latest forensic innovations from academia that can be applied by frontline policing. Register here.